THE TROUBLE AT RYCOTE

Annie Baxter boarded the Augusta Jessie, a convict ship on its maiden voyage to Tasmania in September 1834.

Annie was not a convict though, she was the new wife of Lieutenant Andrew Baxter of the 50th Regiment on Foot who would oversee the cargo of convicts bound for the colonies. Annie kept a diary, making almost daily entries – detailing the weather, the books she was reading to pass the time, her failed visit to the dentist for a tooth extraction and little quips about her new husband.

Her experiences aboard the vessel were quite different to the 200 odd convicts that made the journey with her – she made only a few mentions of the convicts aboard in her diary. One entry around Christmas when a group of convicts sang hymns at her door and two short notations on the death of two of the convicts. But this story isn’t about Annie – it concerns a man who made the journey with her, a man who lived below decks, a man who may have even sung her a hymn on Christmas eve.

Eight miles west of Port Fairy on the road to Portland sits a stretch of craggy cliffs facing the Great Australian Bight. As some of you would know, Port Fairy was known by another name until 1887 – Belfast. Named by John Atkinson, the man who originally purchased the land where the town now sits, after his hometown in what is now Northern Ireland. This story starts late in 1887 – when the town was still called Belfast. On the 31st of October 1886, Isaac Irvine, having finished his labouring for the day on the Aringa Station, headed for the beach near the Crags.

As he neared the shoreline, he stumbled across the body of a man body lying 100 yards from the cliffs. Being sure not to disturb the body, he went back to Aringa Station and sent the groom, Frederick Fry into Belfast to fetch one of the local constables. Constables John Keyth and James Page left for the Crags – finding the body of a man in his 70s, fully clothed with a hat on lying on his side with his head facing towards to cliffs.

The constables made their examination of the scene – finding no marks of violence on the body and only two empty glass bottles on his person. Constable Keyth believed the body had been there for approximately a week or so, given the state of decomposition. They knew the man – his name was William Archer, who had been in the area for 30 years or more, living a solitary life on the craggy cliffs. He had made his living making brooms and mats from grass he collected from the area surrounding his modest hut, situated on the hummocks above the rocks.

The constables had the body removed to the Union Inn at Belfast, where an inquest was to be held the next day. You may be thinking, why would the publican allow a body in a state of decomposition into their establishment? They didn’t really have much choice in the matter. Legislation stated that they were obliged to make their premises available for coronial or magisterial inquiries and for the storage of the deceased’s body. They were compensated £1 for each body received – but, if they refused to receive the body and provide a space for the inquest to take place, they could be fined up to £5.

During the inquest, John Baird, a doctor or ‘legally qualified medical practitioner’ – presented the result conducted a post mortem examination he had earlier made on William Archer’s body. The cause of death – old age and exposure. As you can imagine, this was not a lengthy inquest – given the cause of death determined by Dr Baird and the absence of any suspicious circumstances. But – two men, who had known William Archer for years, provided details of his past that he had confided in them in years gone by that goes some way in explaining why William Archer chose to live the life of a hermit on the craggy rocks outside Belfast.

Buckinghamshire, 1833 – William Archer, a young man in his twenties, unmarried is living with his parents in the small hamlet of Shabbington. It’s New Year’s Eve and William, his mates George Verey, James & Jon Nelmes, Thomas Stevens and Joseph Tipping are at the Barley Mow, one of the local taverns. They’d all been drinking quite a bit and Tipping was described as ‘fresh’ – something that seems to translate to ‘pretty drunk’ in today’s language.

Around 9PM William Archer and George Verey left the tavern and headed to William Southam’s land nearby to do a spot of night fishing – meanwhile Joseph Tipping is a little fresher than before and decides to have a nap under the window at the front of the Barley Mow. He doesn’t nap for long, and Tom Stevens wakes him and helps him on his way home.

Early the next morning, January 1st 1834 the gamekeepers of the Earl of Abingdon, Lord of Rycote Park were patrolling their master’s grounds when they were set upon by William Archer and his mates. Armed with pistols and described as men of ‘indifferent character’ – they assaulted the gamekeepers, beating one of the men to the point that he had to be carried away by is fellow keepers once the ordeal was over.

It wasn’t long before the men were apprehended – James Nelmes was questioned the very next day and by the 6th of January William Archer and George Verey had been arrested. John Nelmes and Thomas Stevens were in custody within the week.

Long story short, it didn’t end well for these young men – while Thomas Stevens and John Nelmes were freed, Archer, Verey and James Nelmes were convicted and sentenced to death, with their sentences being commuted to transportation for life. They were to be sent to Van Diemens Land.

Now, while this form of punishment would be considered harsh by today’s standards – it was fitting for the time and for the crime. Well, it would be fitting, except – that wasn’t how the events unfolded. These men were innocent.

Let’s rewind a bit - back to the Barley Mow on New Year’s Eve 1833. William Archer and George Verey have left the pub to go fishing, and Thomas Stevens is helping out his mate Joseph Tipping who has got pretty merry and decided to take a snooze under the window outside the tavern.

It’s December in England…the middle of winter, and it was a bit of a walk back home for the two men so they decided to spend the night in a nearby cow house owned by farmer, Baldwin Greening. To their surprise, the cow house was already occupied. Verey and Archer had given up on the fish and, most likely for the same reasons as Stevens and Tipping, decided to stop overnight in Greening’s cow shed too. But – there was room for all four men so Stevens and Tipping found a cosy corner to sleep of their New Year’s celebrations. Tipping awoke cold and ‘more sober’ – and decided to use Archer’s feet as a pillow, something Archer complained of a number of times during the early hours of the morning. At 7:30 AM – the men awoke and went on their ways home.

As I was reading through the documents from the National Archives I kept thinking to myself – what a stitch-up! How could these young men get the blame for the assault on the gamekeepers?

Archer’s friends felt the same way – a miscarriage of justice was underway and they had to do something about it. They issued a public notice asking for donations towards the cost of skilled counsel to investigate the matter and get Archer and his mates off the charges. George P Hester was his name – and he did a tremendous job in interviewing witnesses, gathering clues and making his case to the Home Office.

What follows is the conclusions that George Hester made in relation to the case.

The boys were well known to the gamekeepers, it was a small community and young men at the time looked up in awe to gamekeepers – and it was a bright night, not quite a full moon but enough light to make out what was going on around you. So – why did it take so long for Archer and his friends to be identified and apprehended? Presumably, the keepers could have given their names to the authorities right away. And, given this – why did the boys not attempt to conceal their faces or to flee the area after the crime was committed. In those days, minor theft could see you transported, so they would have known very well that assaulting the gamekeepers would see you at the end of a noose, or on a ship to the other side of the world.

When the case was heard at the Oxford March Assizes in 1833, George Tipping, who had spent a cold New Years Eve in the cowshed with Archer and his mates, stated that he was positive that no one left the cowshed until they all went on their ways around 7:30 AM the next morning. Tipping told George Hester in July 1834 what when he gave this evidence at the hearing the judge “was very angry with me because I would not say I fell down when I went out of Lively’s, he threatened to commit me and I was very much frightened”. It seems the judge had in his mind the idea that Tipping was a bit more ‘fresh’ than he was. Where Tipping had previously stated he had taken a quick nap under the window at the tavern, it seems that the idea of Tipping taking a tumble outside the tavern played better with the prosecution’s case.

At the March trial, the keepers at Rycote Park testified that they were set upon twice by Archer and his accomplices and that they never struck a blow in self-defence against them. Hester wrote:

“Is it credible that four active men even they had not been as they unquestionably were in the defence of their master’s property and in the exercise of their just rights would they under circumstances less urgent have suffered themselves to have been beaten and knocked down like sheep?”

He makes a good point too – four gamekeepers whose sole purpose was to protect their Lord’s property didn’t put up a fight when attacked? It came out after the trial that Benjamin Ward, one of the keepers, struck one of the poachers but claimed he was so weak from the blows he had received to do any damage.

What’s the significance of this? Archer and his mates did not have any wounds when apprehended, not a scratch. Surely if a group of fellas in their 20s went up against the gamekeepers Marquis of Queensberry style, both parties would have something to show for it. Further to this – a man named John Hawes, of Oakley, was attended to by a local surgeon William Knight on the 2nd of January. Hawes had a nasty head wound, and when questioned by Hester, Knight said he did not believe Hawes’ story as to how the wound had been received.

So – we have a suspiciously long time between the attack on the gamekeepers and the apprehension of the young men, a fairly solid alibi for Archer and his friends and plenty of information that just doesn’t add up. If there is still more reasonable doubt required in this case, it may come from the confession of a man described by Hester as a ‘hardened villain’, Mr William Shirley.

Shirley held acquaintance with a gang of men from the town of Oakley, only a short distance from Shabbington and Rycote Park, where the assault took place. John Auger, a stonemason, was present at a hunt a few days after the court hearing and was asked by Shirley how Archer and his mates got on at the Assizes. Auger said that they were to be transported, adding that the punishment fits the crime if they had done it. Shirley responded by saying “they are as innocent as you or a child unborn, we can show you the marks as we had from the keepers at the time”. Auger went on to tell Hester that Williams Hawes of Oakley had said to him “you may depend upon it Master Auger that an Oakley party were the men as done it and they’d come forward in a minute and clear the others if they were not afraid of being took up”.

Wow.

There you have it. Two innocent men sent to the other side of the world for crimes they did not commit. While you can imagine that miscarriages of justice like this were perhaps common at the time – but you would also hope that in those cases there was at least some shred of evidence for their guilt.

With a sentence of transportation for life given, William was moved to the prison hulk ‘York’ located at Gosport, near Portsmouth in Englands South. Gosport was just over 100km as the crow flies from Shabbingdon, William’s home town, and would have been the furthest he had travelled from his home all his life. A young man from Buckinghamshire, he had most likely never seen the ocean until he arrived at the port town and found his new accommodation floating in the Portsmouth Harbour.

Prison hulks, which differed from prison ships in that they were not seaworthy at all, were not pleasant places. A convict by the name of Henry Adams complained of the conditions on the York in 1826, just eight years before William’s arrival, by stating “Convict Hulks are totally forgotten Places teeming with every Crime that can degenerate a Man” – he also accused the hulks superintendent of reading his letters for fear that he would expose the cruelties of hulk life.

On 27th of September 1834, William was aboard the Augusta Jessie, making its way out of Portsmouth harbour on the journey to Van Diemen’s Land.

Nowadays we baulk at the 24 hours it takes to get from Australia to England – but can you imagine being on a convict ship for four months, sailing down the guts of the Atlantic Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope and all the way across most likely getting as far South to make the most of the favourable winds while avoiding icebergs to make good time to Hobart.

Shabbington to Gosport would have been a journey for Archer, and now he found himself thousands of miles away from his home, stuck on a cramped ship with 200 other convicts. Fortunately, one of those other convicts was his mate, George Verey. Surprisingly, as bad as the conditions were, only three convicts died on the Augusta Jessie as it made its way to Tasmania. Even more surprisingly, less than 600 convicts died during the period where transportation was used as a form of punishment.

The Augusta Jessie arrive in Hobart on 22nd January 1835 – and the very next day William penned a letter to his parents back home:

“I write these few lines, hoping they will find you all in good health, as it leaves me at present, thanks to the Almighty God for it. I have to inform you that we have, after a voyage of nearly four months, arrived safe at Hobart Town. We came in sight of land on Wednesday, the 21st day of January, and reached Hobart Town on the following day about three o’clock in the afternoon. The appearance of the country as we passed was very rocky and mountainous, interspersed with a variety of rich and picturesque scenery; and, according to accounts, the country is fertile and productive. We are all of us in daily expectation of being engaged by masters for employment, which in my next letter, which I shall write in two or three months time, I shall then give you a more full account”.

If a full account was ever sent back home, it was never published in the local Buckinghamshire papers – though another letter was published in the Oxford City and County Chronicle in July 1837. William did not provide any detail of the past two years spent in the colonies, but rather provided a glimpse of the frustration he felt in being so severely punished for a crime he was innocent of. “If any kind gentleman knew the anxiety of an innocent heart, banished from his parents and native country forever, indeed it is enough to break a heart of stone”.

William’s convict record shows that he was engaged to work for a man named Lawrence. Convicts were generally assigned to landowners or businessmen who required cheap labour. William Lawrence Esq owned 320 acres on Bruny Island overlooking Variety Bay, but farming was not his main trade. He was a pilot – a river pilot. An important job – guiding incoming vessels bound for Hobart through the southern inlets and up the Derwent River.

During his time on Bruny Island, William, while not being a criminal before arriving in the colonies, came to be what some might call a product of his environment. That is, he misbehaved a little bit. His convict record records a number of offences over the years, receiving a total of 96 lashes between 1837 and 1841 – 36 for misconduct, 36 fighting on the Sabbath and assaulting a constable and 24 neglect of duty.

William was granted a ticket of leave in April of 1843 – something akin to being granted parole nowadays. William would have been allowed to work for himself and share some of the freedoms of the colonists in Tasmania, but he would have still been required to stay in the local area, report regularly to the local authorities and…attend church every Sunday!

In 1849 William was granted a conditional pardon – the condition? He was never to return to England. William appears to have made up his mind pretty quickly that a life in Van Diemen’s Land was not for him – and boarded the brig ‘City of Sydney’ bound for Victoria shortly after receiving his pardon.

The City of Sydney had two scheduled stops, Portland and Port Fairy – rough seas in mid-September would see the vessel blow out to sea and losing its anchor, but the City of Sydney made it into safe harbour. Another vessel, the Eagle met with equally stormy weather and when stories of the trials of these vessels reached the insurers in Sydney, they were eager to up the premiums on ships passing through that stretch of ocean by half a per cent.

Perhaps due to the solitary life William lived in later years, he didn’t leave much of a trace of his time in Victoria between his arrival in Port Fairy in 1849 and his death in 1886. Though, there were some contemporary accounts of William Archer, or "Billy Crayfish" as he was known locally.

A brief account of his life locally was printed in Belfast Gazette in November 1886, shortly after William’s death. It stated that William did not always stay in the same place, though he had spent most of his time at The Crags, which looks out onto Julia Percy Island.

“He was in the habit of taking fish to the neighbouring land-owners and in return would receive rations. When he essayed to town with his fish, brooms, etc., he generally stayed a few days during which he generally had his wee "spree", but he was a harmless old fellow, and possessed a civil tongue”.

“The old man was a favourite with many, and was well known to sportsmen who visited the coast on fishing excursions. He was never more delighted than when showing strangers where to obtain the best fishing, and how to secure the famous trumpeter fish, and his nets and lines were always at the disposal of visitors.”

“A couple of years ago an attempt was made to induce "Billy" to come into the Belfast hospital for the winter months, where he would receive the necessary comforts to help to build up his shattered constitution. He declined to leave his solitary hut where he was monarch of all he surveyed in his own imagination. The residents in the locality more than once offered to get "Billy" a crib to reside in, but he declined the friendly intentions”.

Quite remarkably, and perhaps providing a sliver of long-overdue justice, William had told some of the locals that he had received word in the 1870’s that a man had made a deathbed confession back in England, implicating himself in the crimes committed back at Rycote in 1834 and clearing William and his mates of any wrongdoing.

While I’ve been unable to find any mention of William being pardoned, no mention in the British newspapers around that time, it’s very possible that this man was one of the men that George Hester interviewed back in the 1830s. William had already been pardoned back in Tasmania, though this did come with conditions, so a pardon from the Home Office back in England would mean he was free to return home to Buckinghamshire if he wished.

In fact, it was said that the authorities back in England offered to pay for his repatriation, but as a report in Belfast Gazette around the time of William’s inquest stated “resentment was strongly within his bosom, and he indignantly declined to accept the request to return home, stating his young life had been crushed out by an unjust sentence”.

With William refusing the government's offer, his friends then sent money to him in the hope that he would use it to pay his fare home “but the poor fellow used the cash in gratifying the taste he had acquired for colonial beer, and there the matter ended. It was stated that the friends of the deceased were well-to-do and were anxious for the wanderer to return”.

Their wanderer never returned to English soil, rather William would find his final resting place in an unmarked grave in the Port Fairy cemetery.

William Archer's convict record

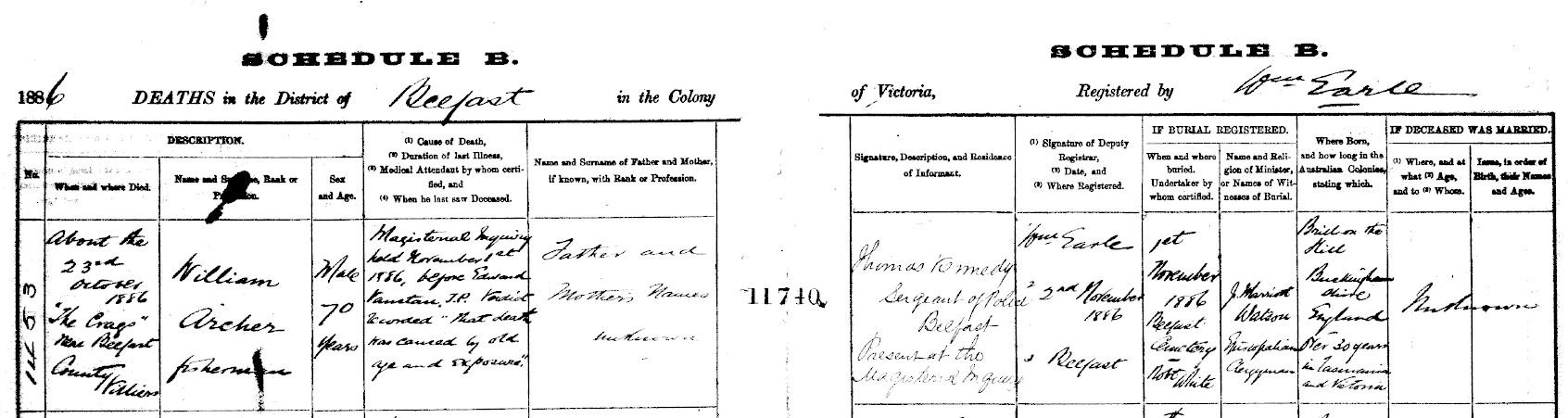

William Archer's death certificate

'The Crags', a rocky outcrop to the West of Port Fairy

Prison Hulk 'York' - in Portsmouth Harbour

The petition made by William's friends