SOCIETY BURNING

Just before 10PM on 1st of March 1891, Robert John Jones was in the office of the North Eastern & Upper Murray Building Society on High Street, Wodonga.

Nowadays you’ll find a Thai restaurant here, wedged in between an adult store named 'Erotic Nights' and an independent school on the corner.

Jones was addressing and stamping a number of envelopes by candlelight. He made the short trip to the post office on the corner of South Street and High Street and returned to the building society to blow out the candle, locking the door before retiring to his room at the Terminus Hotel.

About half an hour later, Michael Golding, a shire employee, was doing his rounds extinguishing the kerosene lamps of the town. He was putting out a lamp in front of the Bank of New South Wales – Wodonga locals will know this building, it’s a homewares store now (previously Wodonga Travel) is now, with those mannequins on the balcony - when he noticed smoke coming from the direction of the Terminus Hotel. He crossed the road and discovered that it was actually the building society that was ablaze.

Golding raised the alarm.

Meanwhile, Jones was enjoying some refreshments with Francis Edmondson, a barrister whose office was between the Terminus Hotel and the Building Society when they heard the alarm. They rushed downstairs to see what all the commotion was. As the men exited the hotel Jones said to Edmondson “It’s your office old man” but as the men got closer they realised, as Golding had, that the building society was on fire.

As Jones bashed the front door down, a thick cloud of black smoke, tinged with red billowed out of the office and the men retreated. Within a few minutes, the entire building was engulfed in flames, attempts by Jones and others to throw water on the blaze proved useless. By this time a crowd of 30-40 had gathered to watch the building be completely destroyed over the next 15 minutes.

Once the fire had burnt itself out, James Mahoney, an off duty police constable who had heard Michael Golding's alarm was on the scene early and began to poke around the ruins – finding nothing but a loose pile of burnt papers and small masonic lodge book…and the fireproof safe. Mahoney, with the help of Constable Mansfield, removed the safe to the police lockup for safekeeping.

When the safe was opened the next day, all that was inside was five blank ledger books. Unbelievably, the society’s most important records, the investors and borrowers ledgers, were not kept in the safe as they were too big. They were kept under the counter and were destroyed along with everything else.

As you can imagine – in a time before central heating, where your only source of heat was a fire, a lot of buildings burnt down. From gold rush days the ‘Act for Preventing the Careless use of Fire’ allowed for an inquest to be held regardless of a death occurring, to investigate the cause of a fire. And so, on the 21st of March 1891 an inquest was opened at the Wodonga Court House.

The police had been investigating the circumstances surrounding the – paying close attention to the timing of the incident. The Society’s Annual General Meeting was to take place on the 4th of March, three days after the fire. In preparation for the AGM, Robert John Jones was requested to provide the societies ledgers for audit on the 2nd of March. In a statement made on the 3rd of March Constable Mahoney suggested this was motive for Jones to prevent the books from being audited for whatever reason.

The theory was that what was recorded in the ledgers was not what made its way to the society’s coffers. Though – Jones played it pretty cool, stating that the loss of the ledgers was not a complete disaster, as the books could be recreated from the entries in the customers passbooks. Entries that matched the ledger.

A notice was put out to all the customers of the society across the region asking them to send in their passbooks so that the ledgers could be reconstructed. Jones stated that he followed the society’s strict rules when taking deposits, in that he never accepted a deposit unless it was accompanied by the customer's passbook for recording the details accurately.

The following month, on the 17th of April, a letter appeared in the Wodonga and Towong Sentinel from someone known only as ‘another victim’. This mystery man or woman questioned Jones adherence to the rules on deposits stating they had a letter from a former resident of Wodonga, and a customer of the society who had paid £7, but only £2 appeared in their passbook.

‘Another victim’ added “Of course I do not even suggest that the misstatement was wilful. Mr Jones may have misunderstood the question, he may have too vivid imagination, or he may be subject to those curious attacks of intermittent mania, which are fashionable just now”.

It was only a week later that a meeting was held with the directors of the society where it was agreed that the building society should be wound up in the coming months. It had only been running 14 months or so. Reports in the local papers stated that the Society had not been a success in its short existence, expenses running much higher than income. Partly to blame, as one paper put it, was that Jones was receiving a £250 annual salary – while interests on the loans given by the Society totalled only £33.

While Constable Mahoney, and no doubt others, suspected Jones of some level of wrongdoing – he was still involved with the Society – preparing a balance sheet for presentation to shareholders at a meeting to be held late in May. It was at this meeting that the society was officially wound up – with debts on the books of £432.

Things were not getting any better for Robert John Jones – with a newspaper report from June 1891 alluding to the old adage that ‘bad things come in threes’. First the fire, then a meeting with angry shareholders and then…divorce proceedings.

Robert was not a bachelor, but a husband and father to three children. His wife, Alice Marguerite Jones filed for divorce in Sydney on the grounds of cruelty. The court hearing was reported on with tremendous detail – revealing Jones as a violent man, assaulting his wife on a number of occasions, kicking her out of their room and sometimes even their home in the middle of the night, only allowing her back in when she started calling out for the police.

She had left him a number of times since they married in 1886 at Bowral, where her mother lived. It was the safety of her mother’s home that she would return when she left her husband on various occasions. The last time she left was in July of 1890 – only six months after Jones had arrived in Wodonga to drum up interest in a proposed abattoir just outside of town.

Jones did not appear at the divorce proceedings, offering no defence to the torment he put his wife through during their five-year marriage. Needless to say, the divorce was granted.

Perhaps the saying should have been bad things come in fours. Jones was at the local court once more in July to bring a libel case against the editors of the Sentinel. Jones did not take kindly to the letter from ‘another victim’, casting doubt over the correct recording of deposits at the society – and he believed damages of £500 would be enough to make up for the damage done to his name. Unfortunately, a jury of his peers took only a few minutes to disagree with him and the case was dismissed.

While Jones was busy being divorced and taking the editors of the local paper to court, many of the customers of the society had returned their passbooks, allowing for a reconstruction of the ledger that was destroyed in the fire. £179 pounds was found to be missing – and Jones was called on for an explanation.

To allow Jones to defend himself and clear his name, the directors allowed him access to all necessary documents. By the 8th of August, Jones had been unable to provide a sufficient explanation of the shortage of funds at the society and he was informed by the directors that they were intending to press charges.

The next day Robert John Jones left Wodonga and set off for Melbourne.

Jones arrived at Grimley’s Hotel on Brighton Beach on the 11th of August – checking in under the name James Jenkins, with no luggage and - as the licensee Mr Hagg would soon discover – no money. After Jones had asked that the drinks he was enjoying at the bar be charged to his account, Mr Hagg asked how he intended to pay for his lodgings and liquor. Jones said he would be receiving a cheque within days and his account would be settled then. He also let slip that he was leaving for India.

The following evening, Jones entertained the other boarders at the hotel with some lively piano playing – ordering drinks for others and singing into the night.

In the morning Jones came down from his room, and seeing some fisherman down on the beach launching a boat, ran down to assist. He came back to the hotel, had a few words with the owner and headed back down to the beach.

Margaret Jones, no relation, was in her yard when she heard a gunshot coming from the newly erected public toilets on the beach. She walked over to the toilets, and on finding the cubicle door locked, went and fetched Francis Davis, a carpenter who was working nearby. Davis returned with Margaret to the cubicle, opened the door and discovered the body of Robert John Jones – slumped over the toilet seat, a revolver in his right hand.

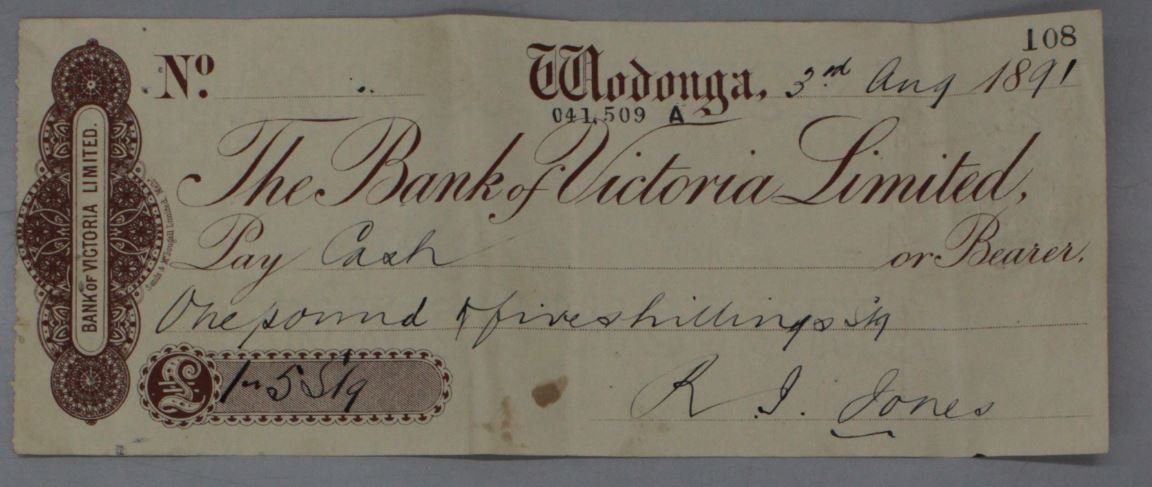

An inquest was held at the Marine Hotel in Brighton the next day. James Jenkins was revealed as Robert John Jones by a Bank of Victoria cheque he carried on him. The inquest concluded that Jones shot himself and that his state of mind at the time was not known. An article in the Age stated that “His demeanour and behaviour was altogether the very antithesis of that of a man who cherishes the design of putting an end to his life”.

Jones had placed a letter in the rack at the Hotel the day before – addressed to D R Lempriere, Barrister at Law. It read as follows:

Dear Sonny

I will be in at 5 o’clock this evening. I am going fishing just now, so wait for me. I waited this morning, but you did not turn up, so I am not going to delay any longer. Fix me up as soon as you can, as I’ll ‘get’ as soon as possible –

Yours Fraternally, James Jenkins.

Who was Lempriere? The police couldn’t find a Barrister of that name operating in Victoria, or anywhere else. He remains a bit of a mystery….

The papers would draw their own conclusions - speculating – and perhaps rightly so, that with his recent divorce, the threat of prosecution for his deeds in Wodonga looming over him and the prospect of life on the run from the law - he could see no other option then to take his own life.

Bank of Victoria cheque, included in the inquest file for Robert John Jones

Report of Jones' divorce

Receipt for cost of holding an inquest

"There are suspicious circumstances and the directors consider an enquiry necessary..."

Letter to D R Lempriere - the mystery man